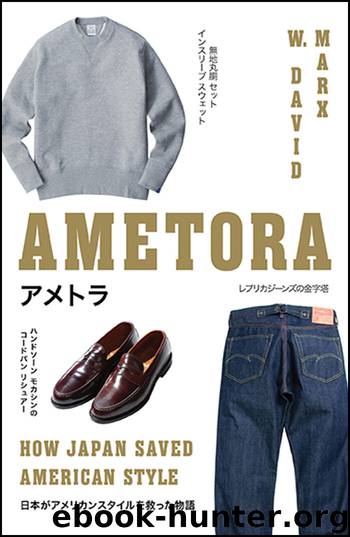

Ametora: How Japan Saved American Style by W. David Marx

Author:W. David Marx [Marx, W. David]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9780465073870

Publisher: Basic Books

Published: 2015-11-30T22:00:00+00:00

Two examples of G.I. style in Men’s Club during the mid-1970s. (Courtesy of Hearst Fujingah)

During the Fifties’ fashion craze, some teens even started dressing like U.S. Army privates—the classic khaki or olive uniforms with short-sleeves, military-tucked neckties, MacArthur-like Aviator sunglasses, and a pointy garrison hat. The teenagers in these outfits did not necessarily intend to glorify the American military, but they certainly cared very little about the antiwar protests of the previous decade. Army uniforms became chic fragments of nostalgia rather than symbols of occupation and imperialism.

In 1978, the hit musical film Grease added even more momentum to the rock ’n’ roll boom, and Cream Soda’s original goods sold ¥300,000 ($5,000 in 2015 dollars) per day. Teens across Japan dreamed of trips to Tokyo just to buy Yamazaki’s pink and neon yellow leopard-print wallets. Five years prior, barely anyone in Japan had ever heard the term “rock ’n’ roll”; now Cream Soda was the best-selling rock clothing shop on the planet.

Needing additional stock of cheap American gear for his new store, Garage Paradise, Yamazaki took his entire staff to Korea on a scouting trip. At a grungy market outside the U.S. military base, they discovered leather bomber jackets piled up for just ¥5,000 ($87 in 2015 dollars)—a fraction of what Japanese rockers paid in Ameyoko for similar items. Yamazaki bought two hundred and requested more be sent over to Japan. The item was an overnight hit, adding to Yamazaki’s fortune and outfitting the youth population in leather.

Cream Soda and Garage Paradise built up Harajuku from a serene residential neighborhood to the national center of youth fashion. Throughout the 1970s, Japanese pop culture had looked beyond Tokyo for its inspiration—the Annon-zoku went to small country towns, Heavy Duty kids looked to the great outdoors, and surfers spent their summers at Shnan beach. The Fifties boom put Tokyo firmly back in the spotlight. At the end of the decade, teens from 100 km away would wake up early on Sunday to take the train into Tokyo, and spend their days strolling up and down Omotesand Avenue and Takeshita Street.

And just like in the Ivy era, youth fashion meant American fashion. But Yamazaki’s Fifties style played so heavily with delinquent motifs and impulses that the fashion market could never perfectly control the consumers. Delinquents would certainly want to decide their styles themselves.

IN THE MID-1970S, BSZOKU GROUPS FROM RURAL LOCALES drove into Tokyo each weekend and slowly rode their bikes up and down the streets of Harajuku. Just like in Shinjuku, the town council endeavored to deter these gangs by closing off the tree-lined Omotesand Avenue every Sunday to become a pedestrian paradise. This attempt to squash one form of delinquency, however, created another. Groups of ex-bszoku, dressed in rock ’n’ roll outfits bought from Cream Soda, gathered in Harajuku to dance to American hits from the 1950s around a ZILBA’P stereo. The men wore black leather jackets, white pocket T-shirts with the sleeves rolled up, worn-in straight leg jeans, motorcycle boots, and topped off the look with tall, greasy pompadours.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Advertising | Annuals |

| Book Design | Branding & Logo Design |

| Fashion Design | Illustration |

| Science Illustration |

Wonder by R.J. Palacio(7750)

Unlabel: Selling You Without Selling Out by Marc Ecko(2989)

POP by Steven Heller(2888)

Hidden Persuasion: 33 psychological influence techniques in advertising by Marc Andrews & Matthijs van Leeuwen & Rick van Baaren(2788)

The Pixar Touch by David A. Price(2744)

Ogilvy on Advertising by David Ogilvy(2692)

Drawing Cutting Edge Anatomy by Christopher Hart(2683)

Slugfest by Reed Tucker(2422)

The Art of War Visualized by Jessica Hagy(2416)

The Curated Closet by Anuschka Rees(2392)

Stacked Decks by The Rotenberg Collection(2283)

365 Days of Wonder by R.J. Palacio(2247)

The Wardrobe Wakeup by Lois Joy Johnson(2238)

The Code Book by Simon Singh(2217)

Rapid Viz: A New Method for the Rapid Visualization of Ideas by Kurt Hanks & Larry Belliston(2200)

Tell Me More by Kelly Corrigan(2200)

Keep Going by Austin Kleon(2170)

Tattoo Art by Doralba Picerno(2086)

Tokyo Geek's Guide: Manga, Anime, Gaming, Cosplay, Toys, Idols & More - The Ultimate Guide to Japan's Otaku Culture by Simone Gianni(1952)